The discussion started with a goal of routinizing the process of sketching 3D objects to a level where it tends to look almost like a natural act – an act that will not require budgeting of continuous high-level cognitive resource. ‘How do we recognize that we have attained this goal?’

Perhaps we should return to the example of the driver who relies on intermittent processing of the situation on the road and also holds intelligent conversation with the fellow passengers simultaneously. He can attend to the conversation when the responses required in driving are fairly routinized due to training and extensive practice of going through similar situations hundreds of times before. ‘How do we make sure that our learner is able to act like the car driver in the story above? Can we create this duality of attention in sketching tasks? In other words, can we truly assess the competence to handle sketching tasks, when the mind is also forced to attend to other matters?’

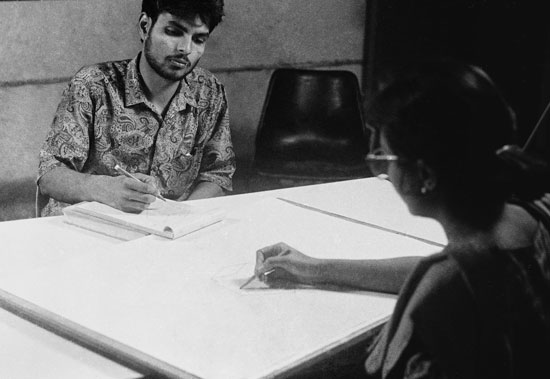

It is possible to create an interview like situation while the learner attends to the principal task of sketching. The partner simultaneously conducts his viva in a familiar but unrelated subject, verbally addressing questions and writing down his replies.

Principal partner works on a sketching task and also simultaneously answer questions asked by his partner

The competence is in maintaining fluency in simultaneously tackling both the tasks. The challenge, on the face of it, looks difficult, but in reality it is not impossible to achieve. Experience with students show that they are able to handle a viva together with a sketching task and perform reasonably well.

Summing Up

The article argued that it is necessary to treat the process of sketching during the early creative phase as a separate class, with its unique rules and style of execution. The role of sketching in creative problem solving is discussed in

Introduction

Act of Sketching

It suggested that if you have to use sketching to support the thought process, the action of sketching 3D objects must become routine and near natural like eating and walking. The aspects like fluency and speed of sketching become important. The sketching during the early creative phase should not demand continuous use of cognitive resource, so that it can be deployed for creative problem solving.

The later discussion focused on

It identifies factors that could lead to near natural sketching. It also suggests underlying principles and an action plan for sketching to become fluent and natural. The ideas were then woven into three anchors.

The first anchor dealt with fluency and included willful control on speed, natural pencil grip, freedom from the direction of drawing of line and developing an internal feel for the path of lines by monitoring body movements. The second anchor concentrated on developing ability to de-link eye movements from the moving pencil point, so that the hand can execute complex motor actions involved in sketching by using kinesthetic feedback. The third anchor dealt with drawing accurate perspective using specially designed underlays and thus developing a feel of perspective space, a prerequisite for effortless representations of objects in perspective. This article concludes with

Judging the Success

This section includes suggestions on how to evaluate the level of competence achieved.

This artice is followed by

dealing with conversion of these observations and ideas into a concrete action plan to help the learning of sketching in steps.